As I walked home from the MAX station yesterday afternoon, inhaling exhaust fumes from cars roaring by, I reflected on my journey as a visually impaired woman. A photo reel of memories began to play as I recalled those first few months following the diagnosis. It was the hardest time: a time when I would walk a mile just to get myself to the nail salon, desperately holding onto preconceived notions of what I thought a normal 22 year old life should look like, trying to comprehend what next. One minute I was singing karaoke with my friends and drinking a PBR, the next I was visually impaired. Going blind.

All I could hear, all I could see, was blind.

I was living in Laguna Beach attending art school at the time. As I stumbled around town that first year, unable to drive, I noticed more in my surrounding world than I ever had before; an irony to the new information I carried with me wherever I walked: I am losing my vision. My world had suddenly turned very, very slow. I wrote blog posts about examining the weeds growing in sidewalk cracks. This was more than an adjustment to transporting myself around — this was a new kind of independence; one not found in whirlwind road trips down the California coast, but in navigating bus schedules. Giving up driving at 22, my suburban American coming-of-age story was rooted in accepting that I had a very rare eye disease and learning how to be content without a freedom everyone else around me had. I am no stranger to the fact that there are worse things happening in the world than me going blind, but still, at the time it seemed like the very worst news I would ever hear.

Ice cream in Dana Point, around the time of my diagnosis.

Those rather bleak first months did, of course, eventually give way to more promising days. Eventually I moved to the Pacific Northwest where the landscapes I'd always painted became real; where seeing one breathless glimpse of God's glorious creation rendered my vision problems not only shallow but inert; where I learned the fine art of living outdoors... of simply living.

I tip my hat to my now-husband for this one. Having met years before we got married, Nick always had a Great Faith that we were meant for one another. Nick was half professional snowboarder and half traveling gypsy. I remember warning him that life with me would mean sacrifices. I remember him not really listening. Because that's how he lives life: he doesn't let excuses get in the way. In time, Nick showed me that going blind was more than an inconvenience: it became my motivation.

Today I work as a personal trainer, helping other people get past their own excuses and discover the joy and freedom found in health and fitness. I marvel at how in the early days, the idea of getting from Point A to Point B without a car seemed unfathomable. Today, I am grateful that my disease not only spurred me to get healthy, but challenged my notions of freedom, independence, and even joy. It is tough to work in a gym as a visually impaired person; there are always unforeseen weights and limbs suddenly appearing in my limited range of vision from out of nowhere; everyone's always giving me annoying high fives that I can't see. But I am in love with what I do. I am helping people. Life is richer, deeper, more meaningful.

For those of you who are unfamiliar with my story, or are perhaps interested in hearing a bit of an update, the following is a brief look at my journey with retinitis pigmentosa.

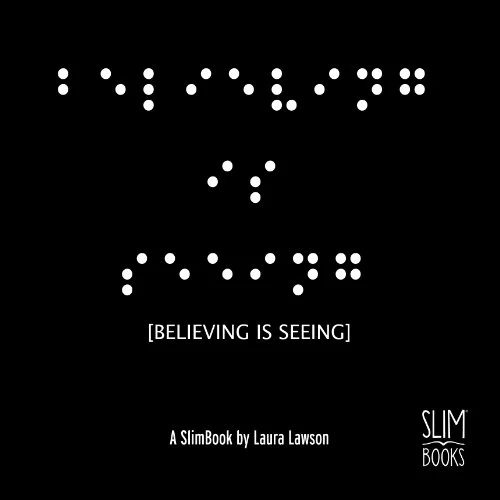

For a deeper look into my story, check out Believing is Seeing, a short ebook I published a few years back chronicling my healing journey and how I reconciled with God. It's only a couple bucks, and 100% of proceeds benefit the Foundation Fighting Blindness.

In 2009 I learned I was losing my vision. "I think you have retinitis pigmentosa," that first eye doctor told me, unable to meet my gaze as she flipped through a dusty old textbook. I had a disease so rare that she had to look it up in a book to be sure. A disease I could barely pronounce. I had her write it down for me so I could practice saying it. Many tests and doctor's visits later, my official diagnosis the following year came through, proving her suspicions correct: I did indeed have retinitis pigmentosa, commonly referred to as RP.

I am not blind, nor do I have "normal" vision. I am somewhere in-between; I am visually impaired.

Retinitis pigmentosa, as Google will tell you, affects the cones and rods in the retina, which are tiny cells in the back of the eye. RP affects the outer layer of the retina first, progressively working its way inward, usually very slowly over the course of many years. The rods and cones in the back of the eye literally die and do not provide light signals to the brain, concluding in blindness or partial blindness later in life. I do not have much of my peripheral vision left, and very little night vision. Normally sighted people have approximately 155 degrees of vision while looking straight ahead (this article does an excellent job explaining peripheral vision), whereas today I maintain only about 24 or 25 degrees of vision (both up and down and side to side) when looking ahead. To put it plainly, I see in tunnel vision.

There is no cure for what I have.

The cells left in my eyes are weakened and have a difficult job transferring information to the brain when going from light places to dark places or vice versa. My eyes work very hard to see amidst even subtle light changes in the environment, working to translate light into meaningful images that my brain can interpret; but no matter how hard they fight or how healthy I eat, the fact remains: I am still losing my vision.

The implications of what I go through are complex and yet simple. I am able to function as a "normal" person quite easily, but certain tasks (like driving) are rendered completely impossible.

Thankfully, hope pervades. There is a lot of hope, as a matter of fact. Whispers of stem cell research have grown louder in the past couple of years, and perhaps even more exciting, the invention of the artificial retina (sometimes called the bionic eye) is beginning to make headlines outside obscure medical journals. Because of devices like the Argus II Retinal Prothesis and others similar, it is unlikely I will ever be completely blind. In essence, companies like the one behind the Argus II are manufacturing a chip wired to the optic nerve in the back of the eye that works like a camera lens, connecting light entering the eye to the brain to create meaningful images. Blind people implanted with the early models of this device are now able to distinguish shapes and read large letters. Medical technology is at an amazing place right now!

For the past couple of years, I have participated in a clinical trial hosted by my ophthalmologist Dr. Duncan at UCSF in San Francisco. There are a couple hundred of us in the study, which is spanning over the course of four years. Reader's digest version... a few people in the study were injected with a particular protein thought to slow the progression of the disease over time. I am in the control group, so nothing was injected into my eyes, but my progression is tracked all the same. The study is using a high quality imaging device to measure the cones in the back of our eyes to determine how they change over time, which will hopefully help Dr. Duncan and her team understand RP and similar diseases. It is an amazing thing to be a tiny part of the movement to find a cure. Every January, I fly down to San Francisco and spend a day at UCSF where I witness the entire trial in action, as a team conducts test after test on my eyes, measuring the change over time. Thankfully, my vision is progressing so slowly that it's almost immeasurable year to year.

I gave up driving in 2009. Legal blindness is defined as less than 20 degrees of vision collectively; I maintain about 25 degrees today. With my doctor's strong urging, I stopped driving by choice, knowing I would be forced to eventually anyway. I did not wish to put others nor myself in harm's way. The years following this decision have involved a deliberate lifestyle change as I have learned what it means to cope and have a career in a society that revolves around freedom, independence, and mobility. I rely on others, my bike, and public transportation to get around.

You may be wondering how I get around on a bike when I do not drive. The answer is very carefully. The way I see it is this: on a bike, the only person's life in danger is my own. Behind the wheel of a car, everyone around me is in danger. Riding my bike is a risk I'm willing to take. I need the independence. Thankfully, a lot of people in Portland are bike commuters like me, so it is a conducive environment to my condition.

These days I don't usually think about my vision very often, as I've gotten used to what it's like to only see in tunnel vision. I have to be extra careful as I move around, particularly in newer environments, but I scan a lot and my brain fills in the information that my eyes miss. Many people ask me if I see black in the peripherary where I've experienced vision loss and the answer is that I do not; I simply do not see anything, same as the boundaries beyond a normal sighted person's range of vision. In day-to-day terms: I do not see objects or people that unexpectedly pop up in my path, like a waiter approaching my table at a restaurant, or someone offering a handshake. I have to be extra careful at nighttime; the built-in flashlight in my iPhone often comes in handy! The central vision I do have left is very sharp and healthy, so unlike macular degeneration or other retinal diseases, I do not suffer from blurry vision (unless I don't have my contacts in, but that's a different story). Many people ask if glasses can help and the answer is a resounding no — people who need glasses are farsighted or nearsighted; the cornea is only slightly misshapen and is easily fixed. My disease is in my retina in the back of the eye, a very different and much more complex area.

I may indeed lose all my vision someday. Not having something in a world that expects you to have that something is a gift, I think. A gift of appreciation, of gratitude, of humility, and especially of faith. There is nothing quite so freeing as acknowledging I am going blind, accepting it, and choosing to live as richly as possible in spite of it. I may be losing my vision, but I'd like to think that I see so much.